Single Knits

Single-knit fabrics can be the most productive knits to produce based on the stitch and machinery. These fabrics offer lots of versatility for garment construction and tend to be used for garments worn close to the body. Stitch constructions bring texture variety to single knits and the weight and drape of the fabrics can be modified by yarn and fiber types.

In this section, we will review a selection of common knit constructions based on the three core stitches: knit, tuck, and float. With so many possible fabric constructions, these core fabrications are the building blocks in understanding the functions of the core stitches to design and innovate your fabric concepts.

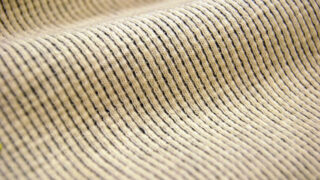

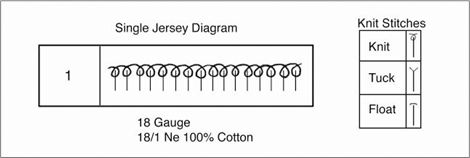

Jersey

Jersey is the most common knit fabric out today found in garments like t-shirts, underwear, and swimwear. It is a very versatile fabric that can come in various weights depending on the use. The extensibility in the width direction is approximately twice the length extensibility.

When cut across the width of the fabric, the fabric curls and runs. Due to the horizontal knitting, this fabric unravels from both ends. Jersey fabrics use the knit stitch across each course. The technical face of the fabric is discernable by the columns of wales throughout, and the technical back of the fabric is discernable by the rows of crowns. The technical notation shows how the knit stitch is used on every needle for each complete course, and every course is the same.

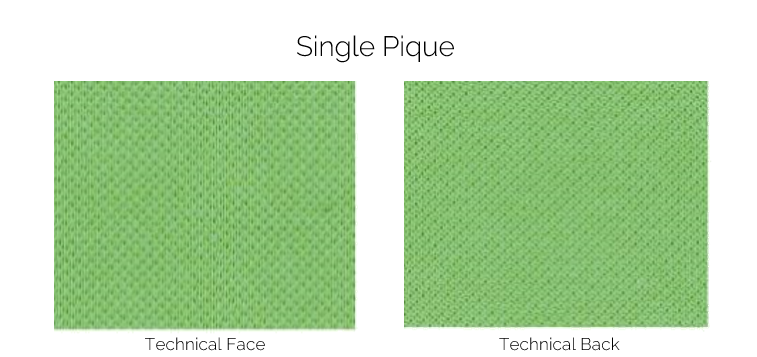

Single Pique

Pique means to pierce or to form a hole or opening. A pique fabric is known for its visible micro-mesh structure (holes), which makes it a great fabrication for warm weather climates. Piques are commonly used in polo knit shirts for this reason and are a favored construction for active apparel.

With a single pique, the technical face is usually the design face of the fabric. Single piques constitute the majority of piques on the market due to being the most productive to knit. The first and third feeds are jersey or all knit stitches. The second and fourth feeds alternate knit stitches and tuck stitches, but are offset from one another. The second feed starts with a knit stitch while the fourth feed starts with a tuck. One repeat of this construction requires four feeds.

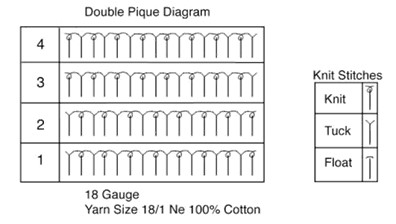

Double Pique

For this type of pique, the technical back is usually the selling face. The construction also needs four feeds to complete the full stitch. In the diagram, you see how feeds 1 and 2 alternate with tuck and knit stitches throughout the course. Feeds 3 and 4 alternate with knit and tuck stitches.

Notice that two feeds are knit on each needle before the needle clears the loops. These held yarns make the fabric thicker than a single pique. The lack of all jersey feeds in the construction makes this pique the slowest to manufacture.

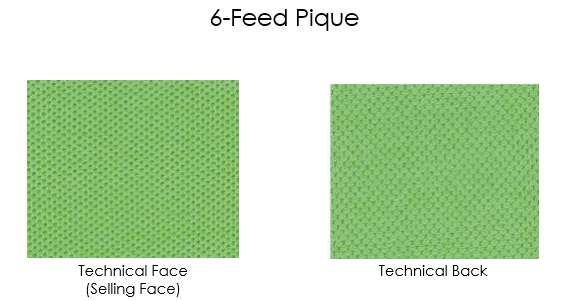

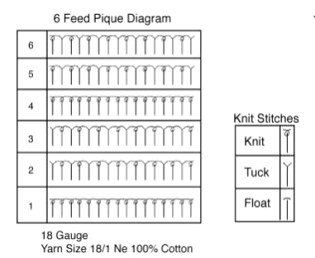

6-Feed Pique

6-Feed pique has a textured look to the technical face and is usually the selling face of the fabric. It requires six feeds to complete the stitch and offers more texture and stability than the double pique.

In the knit diagram, feeds 1 and 4 knit jersey or knit stitches on all of the needles. Feeds 2 and 3 alternate tuck and knit, while feeds 5 and 6 alternate knit and tuck.

This patterning results in two courses stacking tuck loops on top of each other, resulting in a more defined pique cell.

The six feed pique fabric example (technical face) has a similar honeycomb look to the double pique technical back.

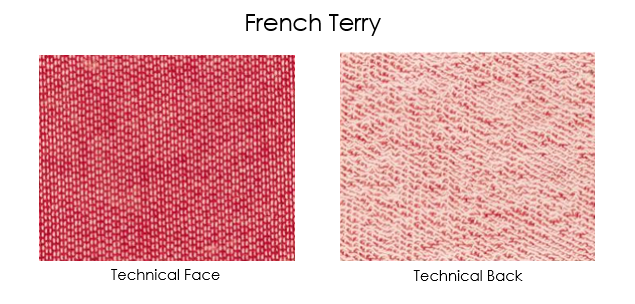

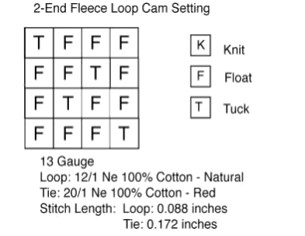

French Terry

This is an excellent example of a fabric containing float loops on the back of the fabric. In the industry, 2-end fleece that is not napped is referred to as French Terry, although it is not technically a terry because floats and not a terry sinker form the loops. As you can see in the notation diagram, this fabric has floats that span three stitches. The other yarn of this 2-end fabric knits only jersey for the technical face.

French Terry comes in various weights and is an excellent fabric for sweatpants, sweatshirts, and other layering sporty garments.

French Terry performs well for all seasons due to its versatility and lack of napping on the technical back. Remember, French Terry is technically an un-napped fleece.

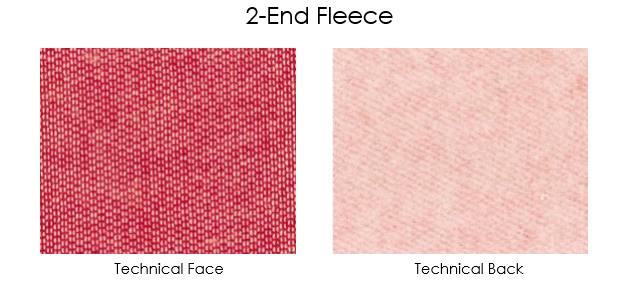

2-End Fleece

The brushing or napping of the interior loops differentiates a French Terry from a fleece. In a typical fleece fabric, the yarns that get napped are knit on the technical back of the fabric as floats. These yarns tend to be coarser and contain less twist than the finer yarns knit as jersey on the technical face. The lower twist in these yarns allows them to be napped more efficiently to produce the fleecy side of the fabric. Notice that the knit structure stayed the same as the French Terry.

Fleece fabrics tend to be heavier and suitable for cold-weather and active garments. Fleece can come in all cotton, cotton/poly blends, or all synthetic fibers.

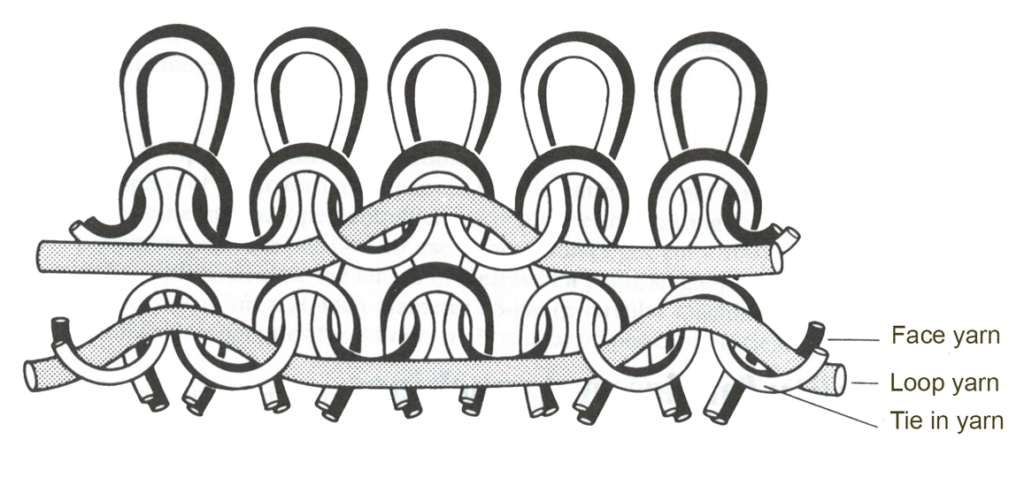

3-End Fleece

Three-end fleece makes the most stable and fullest fleece because it uses three yarns instead of two: a face or ground yarn, a tie-in yarn, and a pile yarn. For the fleece, the loops on the technical back are napped. Cold-weather garments that require extra warmth protection utilize this fabric construction.

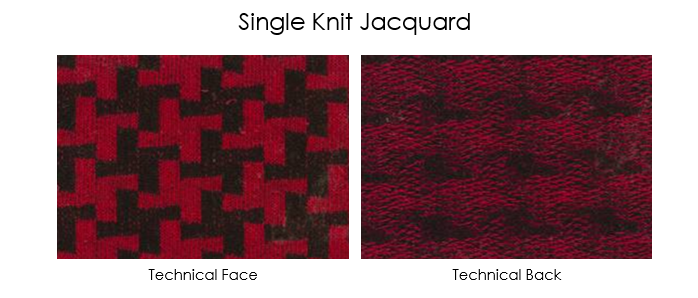

Single Knit Jacquard

Jacquard fabrics offer more opportunities for pattern design in knits beyond the typical stripes from circular knit machines. As you can see in these images, the pattern work on the face is more complicated in this two-color pattern. With single-knit jacquards, the yarn color not visible on the face hides on the back side as a float.

Since floats compose most of the technical back, this jacquard will have minimal natural stretch. In the technical diagram, you see how this jacquard uses all three knit stitches and how the floats hide the second color in each course. The pattern requires two feeds to complete the stitch structure.

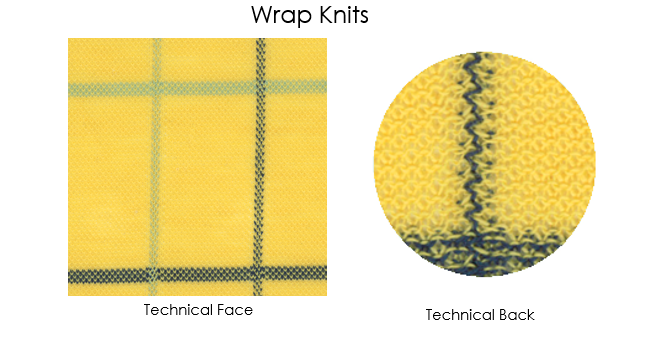

Wrap Knits

Wrapping is the method of producing vertical patterning with warp yarns on a single-jersey knit. Specially controlled warp yarn guides are used to place the yarn into selected needles. If the selected needle rises to receive the warp yarn, it produces pure wrapping.

The fingers or wrapping jacks, with their warp pins, must rotate in unison with the cylinder for each to remain with its section of needles. The wrapping yarns are placed above the needles and remain stationary to feed in a vertical direction.

This technique allows circular knit machines to vary pattern work beyond stripes without compromising the natural stretch of the fabric, which happens with jacquards.

Stretch Knits

Knit fabrics, by nature, have stretch; however, adding more stretch can result in better recovery, which can be achieved using stretch yarns. Spandex is the common synthetic stretch fiber that adds stretch capabilities to knit textiles. Spandex can be added through plating or using corespun yarns in both single and double knit fabrics.

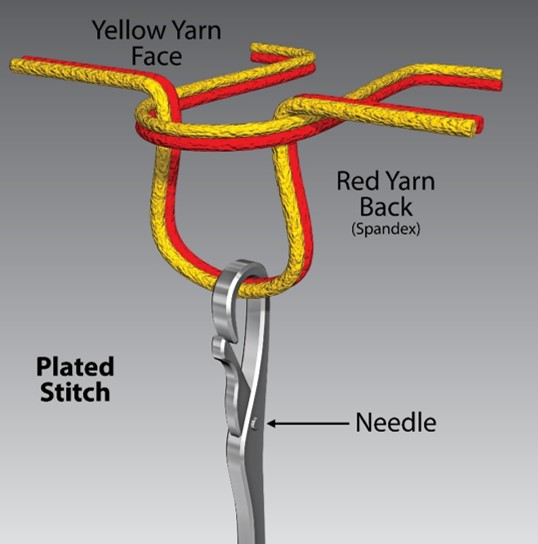

Plating involves making a knitted fabric from two yarns – one appearing on the technical face and the other on the technical back. In the illustration, you see how the yarns are laid parallel to each other, with the yellow cotton yarn at the face and the red spandex at the back. When knitted, the spandex yarn will only be visible on the technical back of the fabric. Plating with raw spandex results in exposing the spandex on the back side of the fabric and producing a shiny effect.

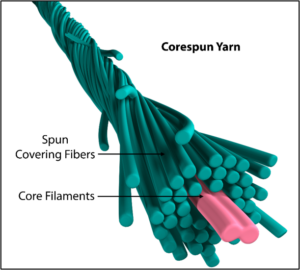

Another option to add stretch with no shine requires corespun yarns. With corespun yarns, the spandex filaments comprise the yarn’s core, and with a second fiber spun around the core to create a more natural finish. This method hides the visibility of the raw spandex and can be knitted into the fabric by plating or in any yarn position.

TERMS TO KNOW (click to flip)

A knit fabric made on one set of needles.

view in glossaryThe basic unit of construction of knitted fabric, consisting of the loop of yarn formed by the needle. The stitch…

view in glossaryA knitting stitch that produces tuck or open effects by having certain needles hold more than one loop at a…

view in glossaryA yarn placed behind a knitting needle so that it does not knit or tuck. Also known as a miss…

view in glossary